Amazigh tattoos are not mere adornments but a profound expression of identity, spirituality, and connection to nature. From the symbolic palm trees and stars on grandmothers’ faces to intricate designs embodying strength, fertility, and protection, these tattoos carried cultural significance for centuries across North Africa. They marked rites of passage, expressed emotions, and served as a silent language of identity and beauty. As modernization and changing beliefs led to their decline, Amazigh tattoos remain a fading yet powerful testament to the creativity, resilience, and heritage of the Amazigh people.

Amazigh Tattoos: Beauty Carved in Memory and History

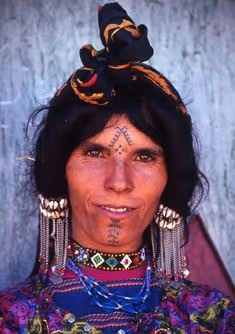

Who among the Amazigh does not remember the beautiful green lines adorning the faces of the grandmothers? The towering palm trees on the forehead, the shining stars on the cheeks, the charming dots settled on the tip of the nose, and all those tattoos that, for many Amazigh, are associated with wisdom, beauty, tenderness, warm songs, and fascinating stories. These are not just ordinary drawings but a memory of an entire history and a unique culture that spanned centuries, only to gradually fade away with the passing of mothers and grandmothers.

These decorative patterns added unparalleled beauty to the faces and bodies of Amazigh women, complementing their sharp eyes, unique beauty, and radiant rosy cheeks.

Across various Amazigh regions in North Africa—from the lush landscapes to the mountains and even the deserts—the Amazigh people replicated nature onto their bodies through tattoos, transforming them from mere adornments into a memory of the body, and from simple drawings into symbols carrying powerful and multifaceted meanings.

The history of tattoos among the Amazigh spans centuries before this practice, which formed a significant part of Amazigh culture for many years, began to decline gradually starting in the 1970s, according to sociologists and anthropologists.

Tattoos: Pain for the Sake of Beauty

The practice of tattooing among the Amazigh was more common in villages than in cities. It was carried out with meticulous rituals by the "washema" "tahjjamt"(tattoo artist), who was chosen based on her talent for drawing tattoos, her speed in executing them, and her mastery of various tattoo shapes.

Many narratives indicate that the Amazigh washema of old were selected for their extraordinary abilities to heal diseases, protect against envy and the evil eye, and break spells and magic.

The washema drew tattoos on the bodies of village, tribe, or family women without any financial compensation. The necessary materials for this process included a needle, kohl, burned soot, salted water, and herbs for sterilization.

In Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, for example, the washema and the girl wishing to be tattooed would sit on the ground, surrounded by other women—relatives, neighbors, and friends—who would observe the process, offer beauty advice, and pray for good fortune and blessings for the tattooed girl.

With great focus, the washema would sketch the desired shape using black charcoal, then begin pricking the outlined area with a needle until blood emerged. The injured area was then rubbed with burned soot and left for some time before being sprinkled with salted water and herbs for sterilization. After a week, the wound would heal, leaving behind a beautiful green tattoo in the shape of a letter, a palm tree, a star, a snake, a spider, or even a fly, all symbolizing a deep connection to nature and the human desire to recreate its imagery on the body.

The Body’s Connection to Nature

Tattoos on Amazigh women often covered the face and other body parts, such as the neck, hands, feet, chest, and abdomen. The density of tattoos on Amazigh women's bodies varied by tribe and by the era in which the tattoos were applied. In ancient times, Amazigh women adorned their faces with abundant tattoos, but over time, they began to reduce them until the practice stopped entirely in most regions.

The symbols used in Amazigh women's tattoos carried profound meanings:

- The tree symbolized strength.

- The plant and the spider indicated fertility.

- The snake denoted the ability to heal from illnesses.

- The fly and the bee represented extraordinary energy.

- The two parallel lines on the chin symbolized the duality of good and evil within every human soul.

By marking and reconstructing the body and inscribing its history, tattoos transcended their cosmetic role to serve social functions, announcing a particular status, role, worldview, or fear of the unseen world.

Tattoos: A Silent Call to Marriage

Tattoos, as a "symbolic mark," were historically applied for identification and differentiation among people. Hence, the Amazigh used tattoos primarily to distinguish adult and married women from young girls who had not yet come of age.

"Tattoos are living art, deriving part of their uniqueness from their bearer—the human body. They are moving drawings with multiple layers, making them simultaneously an artistic masterpiece, a fierce challenge, and evidence of fertility."

To achieve this aesthetic goal, Amazigh women had to wait for two key occasions to get tattoos: puberty and marriage. A third occasion might occur post-marriage, where women could add new tattoos to other parts of their bodies at their husband’s request.

In some Amazigh regions, such as the Rif area in northern Morocco, many girls tattooed their faces shortly before puberty, signaling that they would soon be ready for marriage.

Tattoos: Magical Beauty

Amazigh women did not practice tattooing merely to replace jewelry or appear beautiful. Instead, tattoos carried other connotations. In the Kabyle region of Algeria, for instance, women used tattoos to express certain emotions or indicate their social and familial status, such as hinting at whether they were single, married, or widowed. For example, a woman whose husband had passed away might tattoo a line connecting her chin to both ears, symbolizing her late husband's mustache.

For nomadic tribes across North Africa, tattoos were always a marker of identity, distinguishing members of different tribes. Tattoos placed primarily on the face often served magical purposes, such as warding off bad luck, protecting against the evil eye, and attracting wealth and success.

In some Amazigh tribes in Morocco and Tunisia, another type of tattoo known as "Ahjam," meaning "the healer" in Amazigh, was practiced for therapeutic purposes. Women applied these tattoos on their faces, while men placed them in less visible areas such as the hand, aiming to relieve headaches, abdominal pain, or throat ailments. The only difference from regular tattoos was that "Ahjam" was applied using a knife instead of a needle.

Men: Emphasizing Elegance

Amazigh men also had tattoos, though they differed entirely from those of women in precision and size. When a man decided to get a tattoo, he would turn to one of his female friends who worked as a washerma to draw a light design on his palm or forearm.

The Loss of Identity?

Like many customs and beliefs, Amazigh tattoos began to disappear gradually in different regions starting in the 1960s and 1970s. The last generation to bear these symbols and drawings on their bodies was the grandmothers. As these grandmothers pass away, carrying their oral tales and exquisite tattoos with them, a significant part of Amazigh history and identity is being buried.

The disappearance of Amazigh tattoos is linked to multiple reasons:

- Urbanization and cultural suppression: During the 1960s, governments in Morocco and Tunisia sought to erase traditional roots and combat all things traditional, including local dress, customs, and the Amazigh language, aiming to create an Arabized and ideologically shaped individual.

- Religious influence: While tattoos were always permissible among Muslim Amazighs (unlike Jews and Christians, who considered them forbidden), the Wahhabi wave that gained ground in North African countries during the 1980s and 1990s led many Amazigh women to remove their tattoos using non-medical methods, believing they were repenting for a sin or error.

The Loss of Beauty and Identity

This represents a significant loss for Amazigh culture. Tattoos had an enchanting aesthetic touch, requiring neither expensive cosmetics nor serving merely decorative purposes. They were simple yet profound in their forms, as though we lost part of the aesthetic imagination that distinguished the Amazigh people, just as all peoples on earth possess unique cultural expressions.

Tattoos also served as a communicative record among communities and tribes. Married women could be distinguished from single women or widows through tattoos, and tribal affiliation could be identified by specific tattoo designs.

Regardless of differing interpretations and varied meanings, Amazigh tattoos remain a delicate language expressing bodily desires and showing humanity’s tendency toward perfection and its quest for immortality. They embody a beauty that only death can erase—a beauty crafted from nature, through nature, and for an intimate connection with it. This adornment gave radiance to women’s bodies without hiding their true nature and faces, standing in contrast to today’s globalization-driven masks, cosmetic products, and artificial beauty marketed by brands that view women solely as consumers desperate for complexity and affectation.

Conclusion

Amazigh tattoos are more than mere decorations; they are an art form deeply woven into the cultural and historical fabric of the Amazigh people. As symbols of identity, beauty, and connection to nature, they tell stories of resilience, spirituality, and social bonds. Their gradual disappearance reflects broader cultural shifts, but their legacy remains a testament to the creativity and unique heritage of the Amazigh. By remembering and studying these tattoos, we not only preserve their historical significance but also celebrate the profound relationship between humanity, art, and nature.